I picked up making stewed rhubarb because my mom always liked using the rhubarb grown in her garden to make stewed rhubarb and rhubarb chutney. (Ironically, for this post, and often enough, I use rhubarb purchased from the grocery store!)

Note that this recipe effectively needs to be done over two days, or at least with a pause of several hours (roughly equivalent to a minimum of “overnight” ) between preparing the rhubarb, and beginning to stew the rhurbarb.

Note that I also am using the “packing in mason jars and heat-processing” method to preserve the stewed rhubarb, and to allow for the making of larger amounts of stewed rhubarb at once; once the heat-processed jars have cooled, the stewed rhubarb is ready to eat.

Making the Stewed Rhubarb:

Day one:

After buying some rhubarb at the grocery store, some mise-en-place was done by taking out a cutting board, a mixing bowl, a measuring cup, a kitchen knife, and a kitchen scale:

To avoid confusion a bit later on, the tare weight of the mixing bowl was measured and noted (instead of using the tare function on the kitchen scale):

The rhubarb purchased earlier was taken out (yes, it is a bit shabby!)

The elastics and labels were removed from the rhubarb bunches:

I began to wash and rinse the rhubarb:

The rinsed rhubarb stalks were brought to the cutting board:

The rhubarb stalks were trimmed:

The trimmings were placed in a kitchen waste bucket for later disposal in a municipal composting programme:

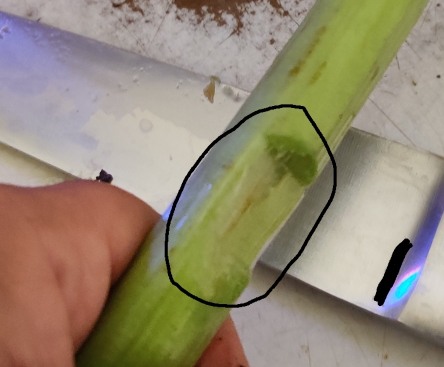

If the rhubarb isn’t completely fresh, or especially typical (in my experience) for commercial rhubarb purchased at the grocery store, sometimes there is some minor damage to the stalks to be removed:

The stalk damage was removed (and while my name can be found on my — this — website in several places, I have blacked it out from my knife, on which I had inscribed my name years ago):

The trimmed rhubarb stalks were piled up …

… and the rhubarb stalks were rinsed again to remove the last of the bits:

Some stalks were laid on the cutting board for chopping:

The rhubarb stalks were chopped using a slicing motion against the grain:

As chopped rhubarb started piling up on the chopping board, it was transferred to the mixing bowl:

The rest of the rhubarb was chopped, and transferred to the mixing bowl as it was produced:

The bowl of chopped rhubarb was placed on the kitchen scale and weighed:

The weight was noted, to be used in a moment:

A large pot and wooden mixing spoon were taken out:

The chopped rhubarb was transferred to the pot:

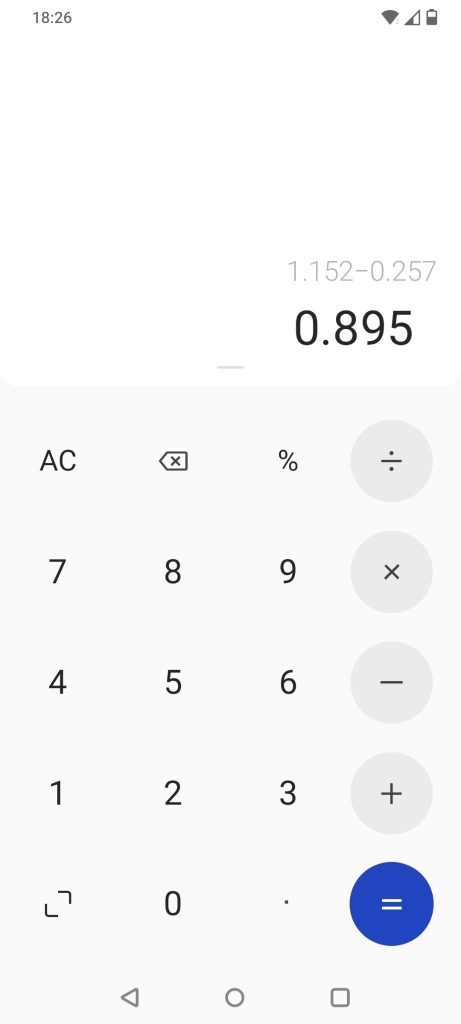

A calculator app was started, and the net weight of chopped rhubarb was calculated by subtracting the bowl tare weight from the weight of the bowl filled with the chopped rhubarb:

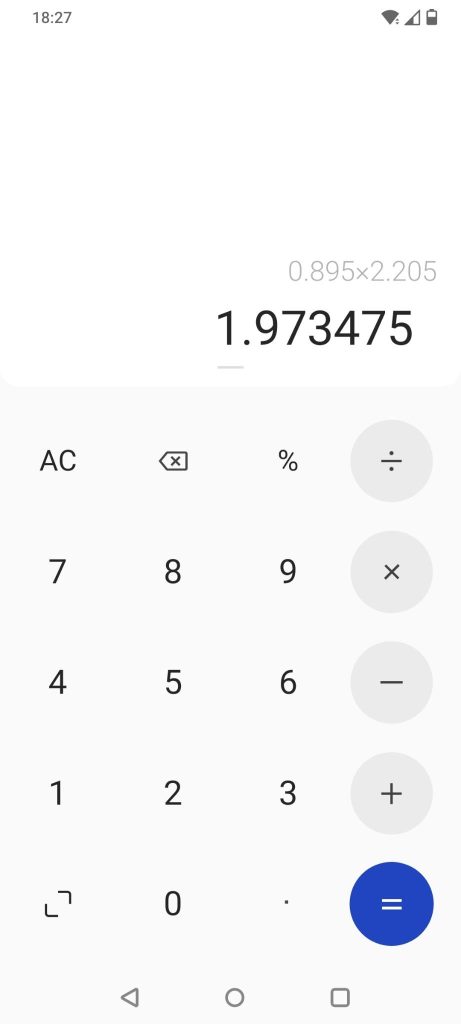

Since my recipe is based on the Imperial system, the weight of 0.895kg (above) was converted to pounds, giving a result just barely shy of two pounds of chopped rhubarb:

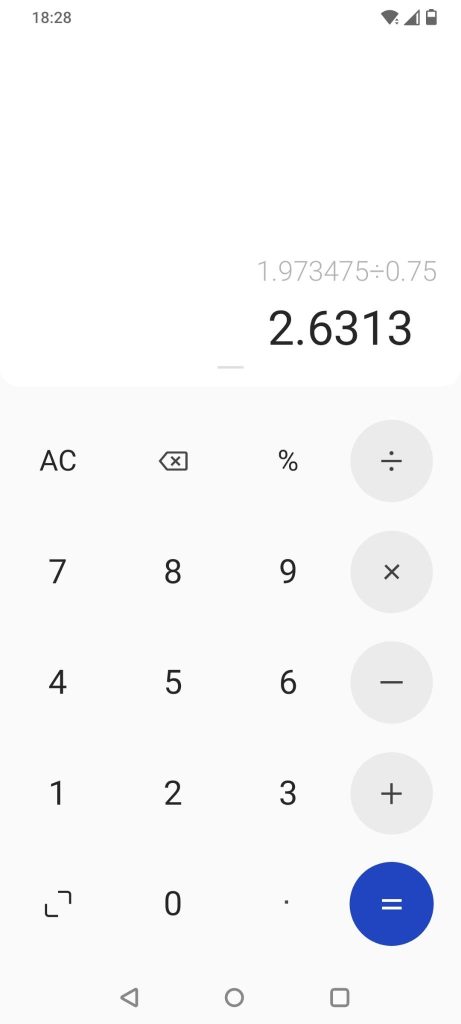

Next, a multiplication factor for how many “recipe units” was calculated by dividing the weight of the chopped rhubarb by the base amount of three quarters of a pound:

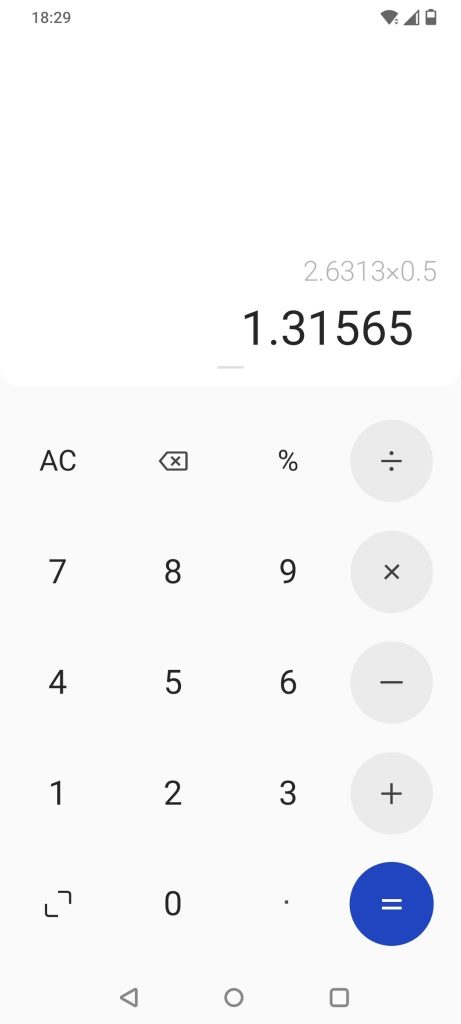

The multiplication factor was multiplied by the required amount of sugar and lemon juice for per “recipe unit” of 3/4 lb of chopped rhubarb: Half a cup of sugar, and half an ounce of lemon juice, resulting in 1-1/3 cups of sugar, and 1-1/3 ounces of lemon juice:

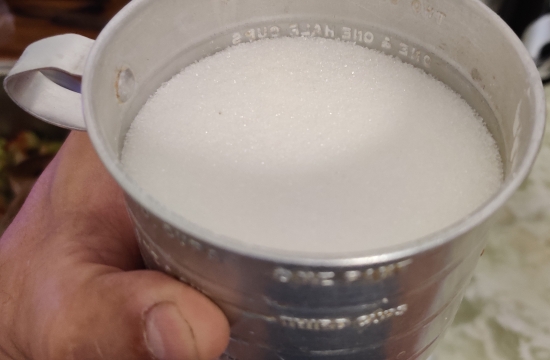

Sugar and a measuring cup were taken out:

Sugar was measured out:

The sugar was poured onto the chopped rhubarb:

The chopped rhubarb and sugar were mixed with the wooden spoon:

Lemon juice was measured out:

Extra sugar was added to the lemon juice:

The lemon juice and extra sugar were mixed:

The lemon juice and sugar mix were added to the chopped rhubarb and sugar:

The chopped rhubarb, sugar, and lemon juice were mixed some more:

A lid was placed on the pot of rhubarb, sugar, and lemon juice:

The pot of chopped rhubarb, sugar, and lemon juice was placed in a fridge overnight:

Day two:

Early the next morning, I checked on the pot of chopped rhubarb:

As can be sort of be seen above and better in the following photo, a good amount of liquid had been drawn by the sugar from the pieces of chopped rhubarb:

The chopped rhubarb was mixed again with a spoon:

The pot of chopped rhubarb was returned to the fridge until later that evening (after coming home from work.)

That evening, a jar wrench, a jar funnel, tongs, a ladle, and a stainless steel flipper were taken out:

Mason jars, a few more than I expected to need, and new lids and lid rings, were taken out, but kept aside for the moment:

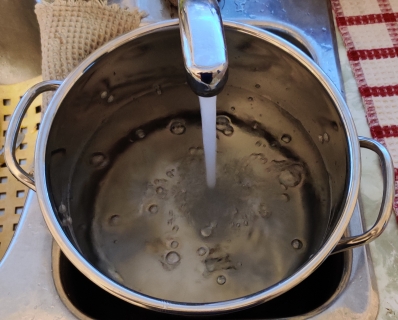

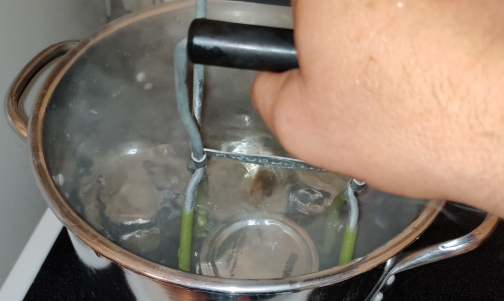

A pot and trivet were taken out, to act as a boiling water bath soon:

The trivet was placed in the bottom of the pot:

The pot was filled with water:

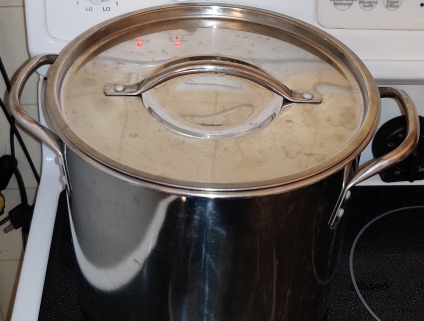

The pot of water was placed on a burner on the stove:

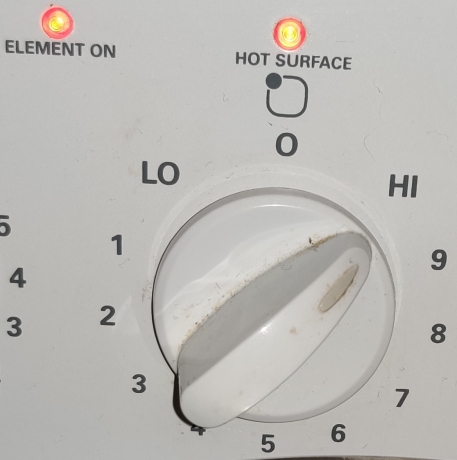

The stove was turned on:

… and the lid was placed back on the pot:

Since I had placed the pot of water on a smaller burner, which proved to be a mistake, I still waited a bit before taking out the pot of chopped rhubarb, sugar, and lemon juice, and placing it on the stove:

After waiting a bit more, having gauged the heating up of the pot of water, the burner under the chopped rhubarb mix was turned on:

The lid on the pot of chopped rhubarb mix was removed:

As the rhubarb mix was heating up, I of course mixed it to avoid burning:

The rhubarb mix began to boil:

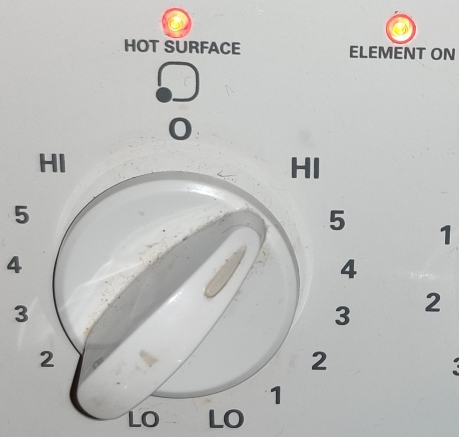

At this point, the rhubarb mix was taken off the burner, and since the water bath had not yet reached the boiling point, I brought it forward to the larger burner to bring it to a boil more quickly:

Fortunately, it was obvious that the water bath was “hot enough” to dip the (clean) bottle funnel to sanitize it:

The bottle funnel was placed in the neck of a jar:

The ladle was dipped in the hot water to sanitize it:

I started ladling the boiled rhubarb mix into the jar until it was filled:

A lid and ring were brought to the jar, and screwed onto the jar (oops, I forgot to take a picture of this second part):

The rest of the boiled rhubarb mix was transferred into jars, and lids were screwed onto the jars:

At this point, the water in the water bath was finally starting to boil:

Using the jar wrench, the filled jars were transferred to the water bath:

Once the water had come to a rolling boil …

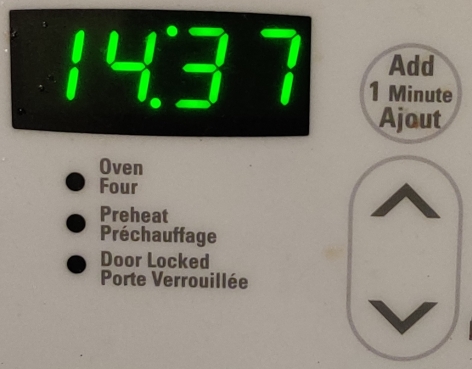

… a timer was set to 15 minutes …

… and the lid was placed back on the pot with the water bath and filled jars:

At this point, the water was boiling so vigorously, that water was splashing out of the pot!

After 15 minutes had elapsed, the filled jars were removed from the water bath using the jar wrench:

The now heat-processed jars were placed on the the cutting board:

Hot water collecting on the jars was soaked up with a towel:

The jars were moved apart from each other to allow for some ambient cooling for a few moments:

Then, the still-warm jars were moved to a fridge to complete cooling.

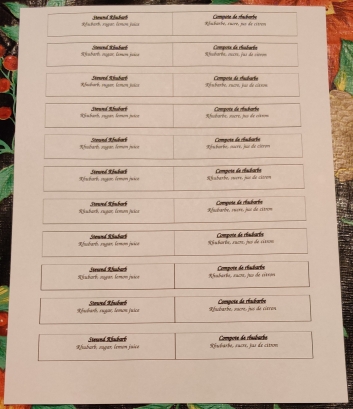

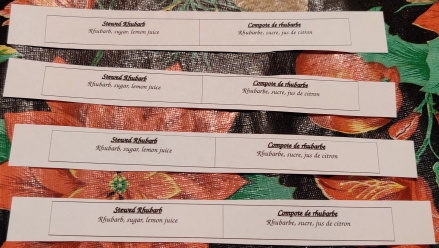

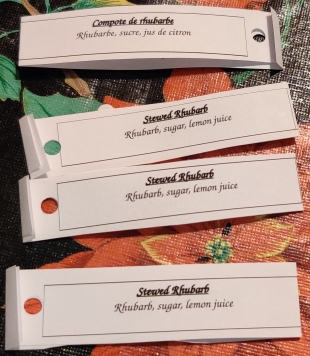

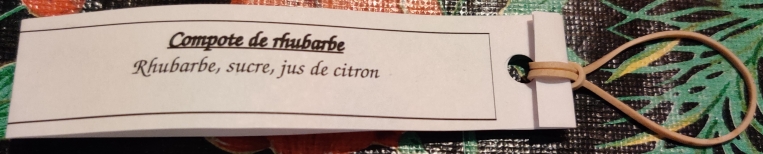

At this point, I changed tack a bit and printed out some labels for the jars, modifying another label template I have for my pickled eggs:

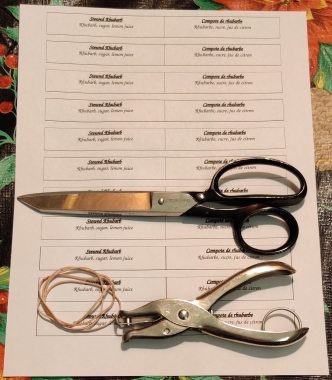

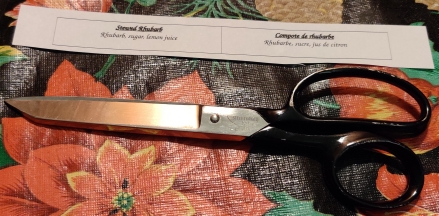

Scissors, a hole punch, and some elastics were taken out:

Four labels were cut from the sheet:

A date code (in this case for 09 August, 2023, the day I filled and processed the jars) was written on the back / inside of each label:

The labels were folded over onto themselves:

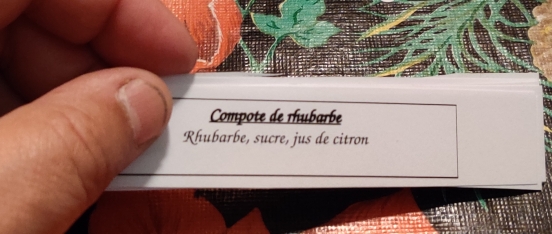

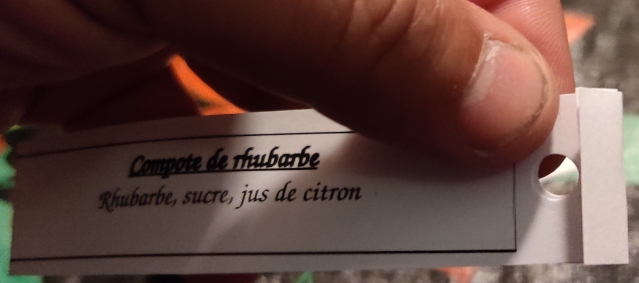

I should note at this point at which the print is more legible, that I live in Montreal, where French predominates, hence the labels are in both English and French. As it happened in the picture above, the folded labels with the English showing were upside down because that’s how I inadvertently happened to flip them over. 🙂

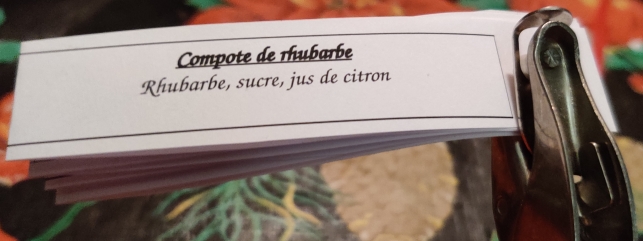

I then picked up the labels, piled them one on another, and crimped the folds:

A hole was punched through the labels on the end opposite to the fold:

On each individual label, the end near the hole was folded over:

Ah here, the English labels are right side up. 🙂

An elastic was threaded through the hole of a label:

The elastic was looped into itself, and loosely tightened to allow for it to at once hold the label, as well as have a loop to use to go around a jar’s neck:

… which was repeated for the other three labels:

The following morning, the cooled (and fully sealed) jars were removed from the fridge, and brought to the workspace where the labels were:

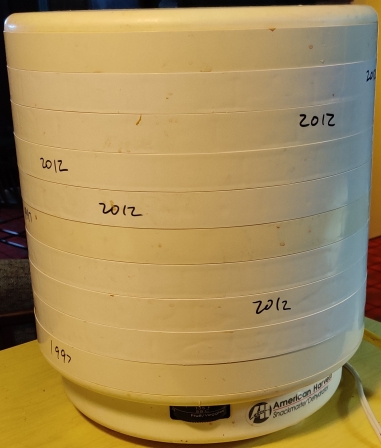

Labels were looped around the jars:

These jars will be kept to be donated to my church’s fall fair, along with a few jars of my pickled eggs! (And, Mom will receive any which don’t sell. 🙂 )